Helbling Robotics Research Lab

7 minutes read •

Helbling Robotics Lab

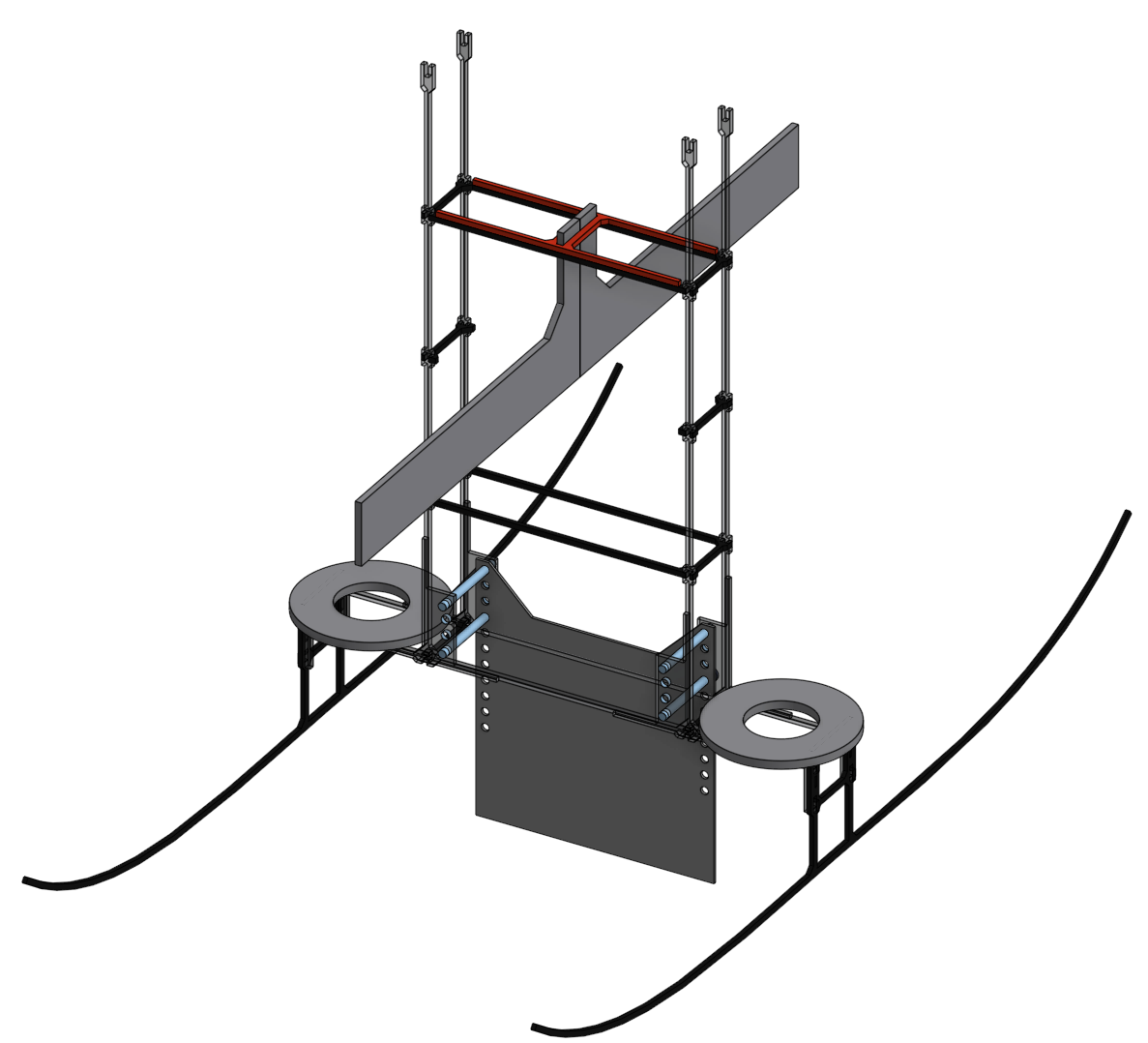

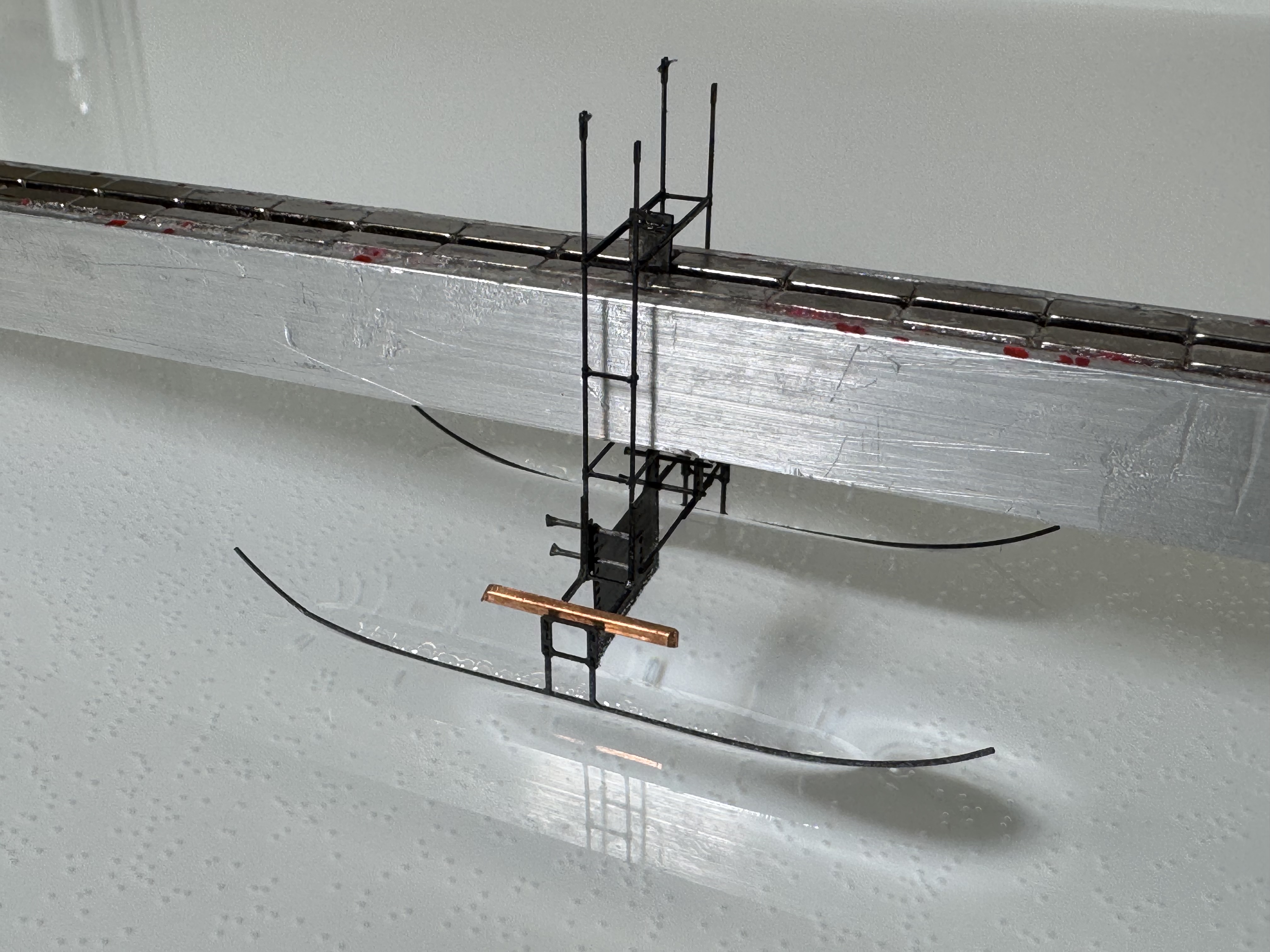

The Helbling Robotics Research Lab focuses on the design of autonomous insect-scale robotic platforms capable of sustained operation in complex real-world environments. I joined the lab during my first semester of senior year and began working on one of the lab’s three robotic platforms, Gammabot, where I am designing and developing a dynamic braking mechanism for the robot. Gammabot is an insect-scale flapping-wing robot that skims along the air–water interface, leveraging centimeter-scale fluid–structure interactions to enable controlled interfacial locomotion.

Final Report

Below is the final report for my senior design project. The remainder of this page summarizes the work and results detailed in the paper. My Systems M.Eng project picks up where this paper leaves off; current progress will be added later in the semester.

Summary

Motivation: A key limitation of the existing Gammabot platform is braking, as the wings cannot provide reverse thrust and the robot relies almost entirely on passive drag, limiting stopping performance and precise station-keeping.

Performance Metrics: The braking system is designed to slow the robot from a measured top speed of approximately 0.7 m/s to within 5% of that value over a stopping distance of 6 cm, approximately one body length, to enable reliable robot-to-robot communication.

Design Constraints: The brake must preserve interfacial operation, avoid disrupting or breaking the water surface, and remain compatible with the mass, size, and geometry constraints of the insect-scale robotic platform.

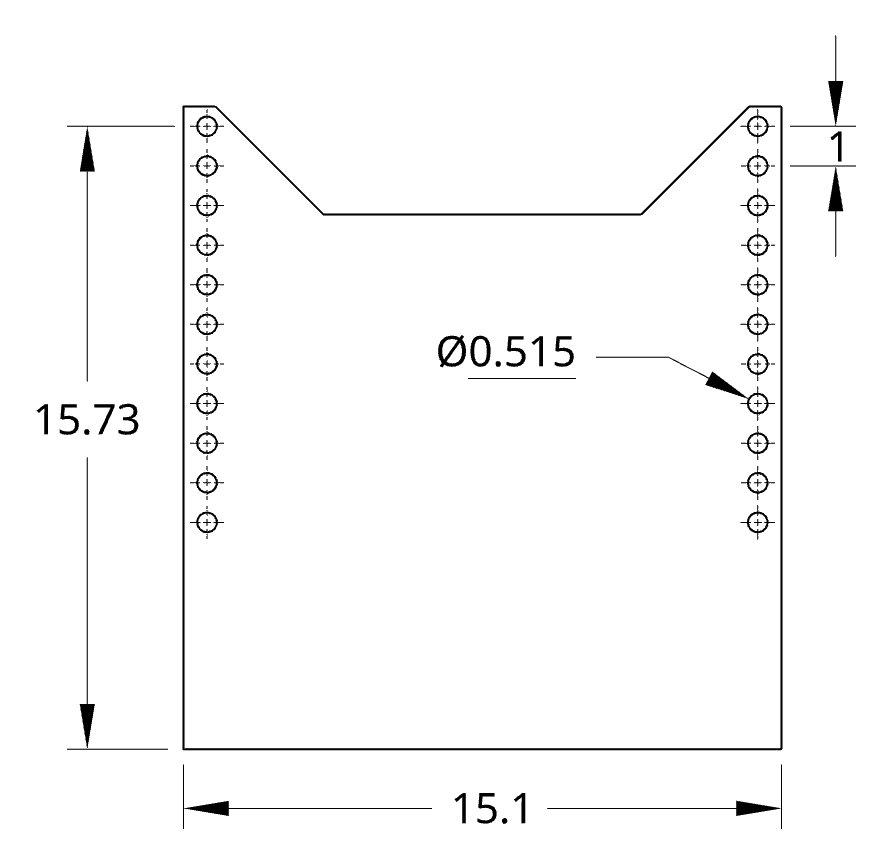

Design Approach: A passive, drag-based water brake is employed, using a lightweight carbon-fiber flat plate partially submerged in water to leverage hydrodynamic form drag rather than aerodynamic or surface-tension-dominated effects.

Modeling Framework: Braking behavior is characterized using a lumped drag constant extracted from velocity–distance data, enabling direct comparison between analytical predictions and experimental results.

Experimental Validation: The braking mechanism is evaluated experimentally using controlled interfacial tests, demonstrating measurable increases in effective drag and reduced stopping distance relative to a no-brake baseline.

Analysis and Modeling

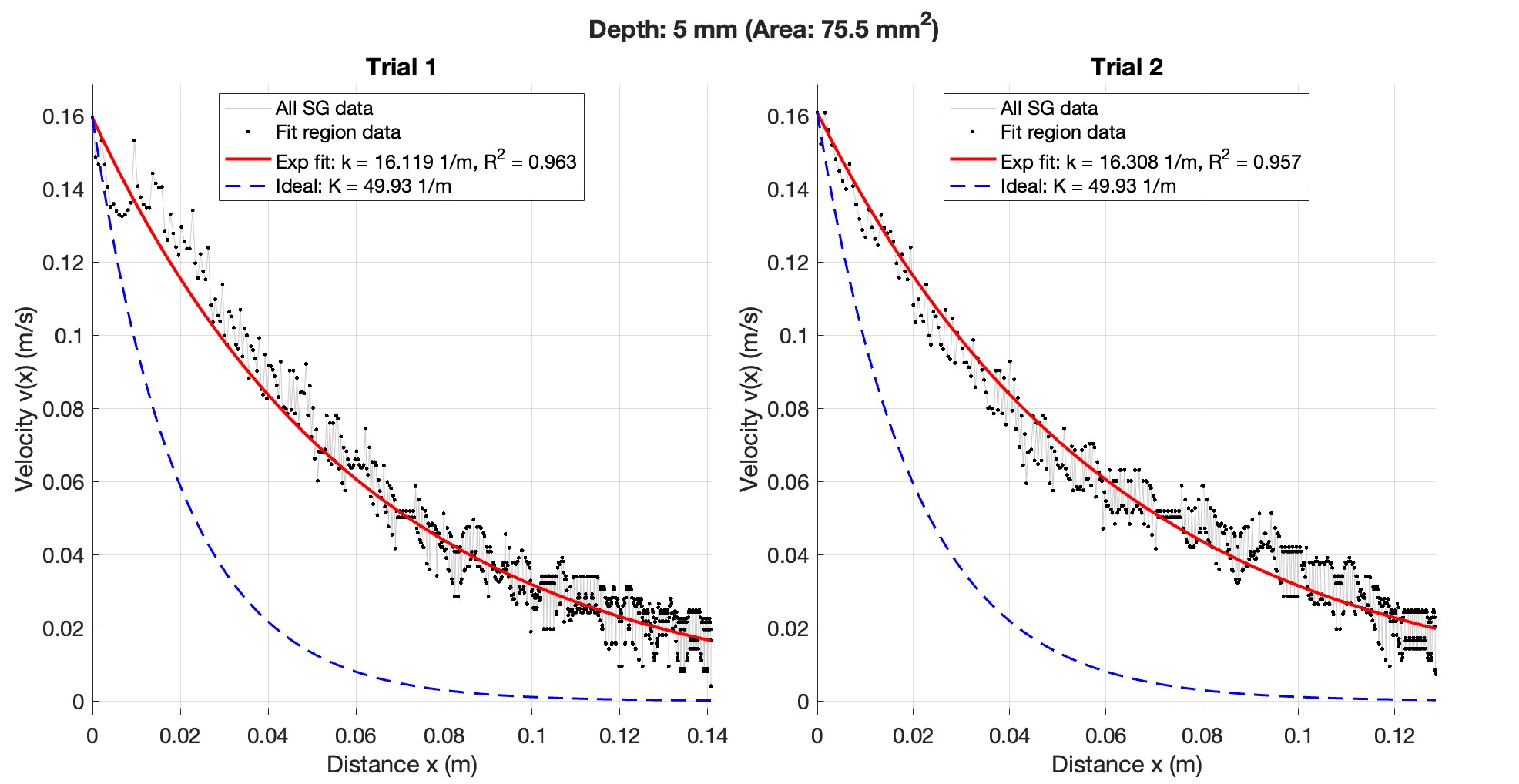

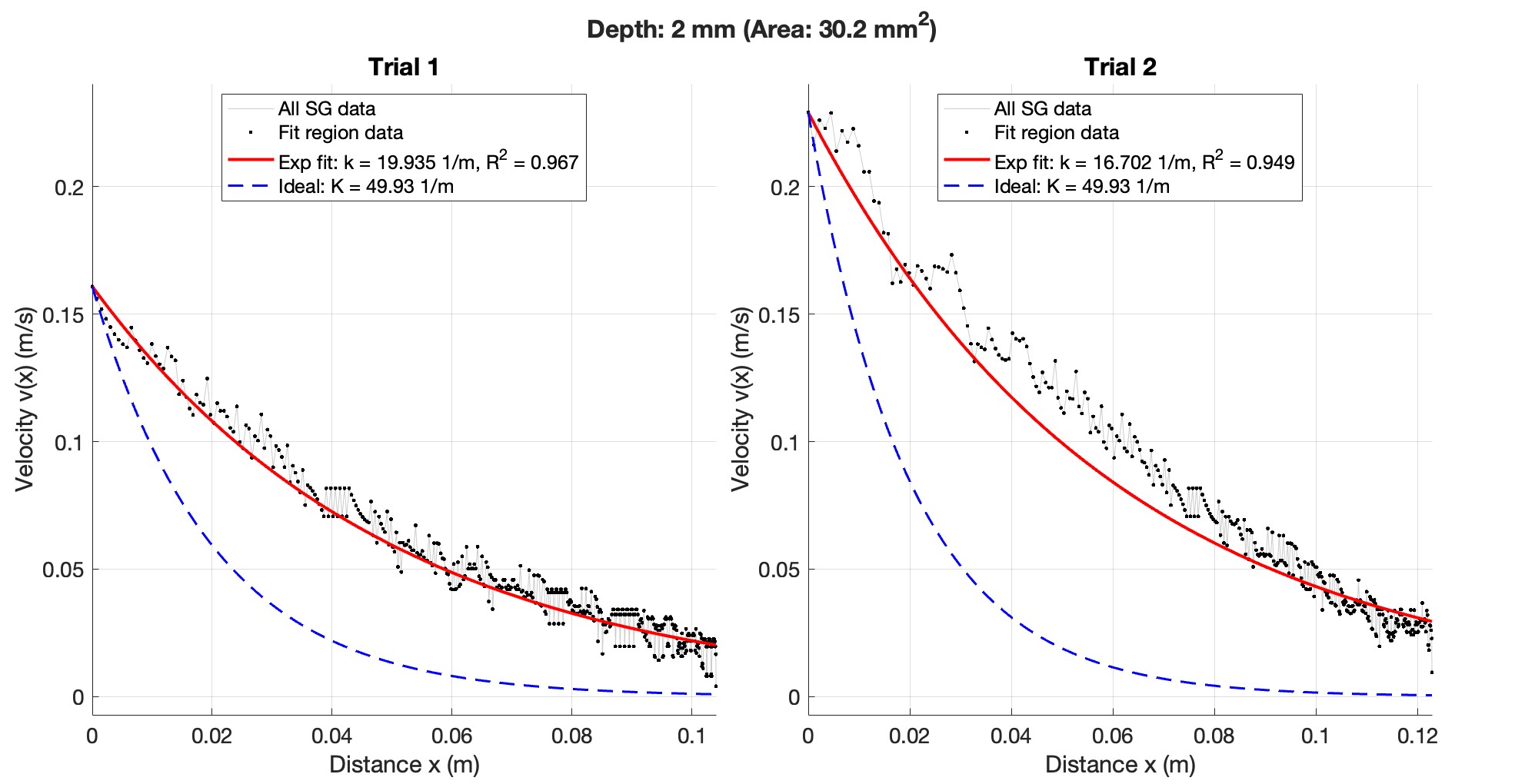

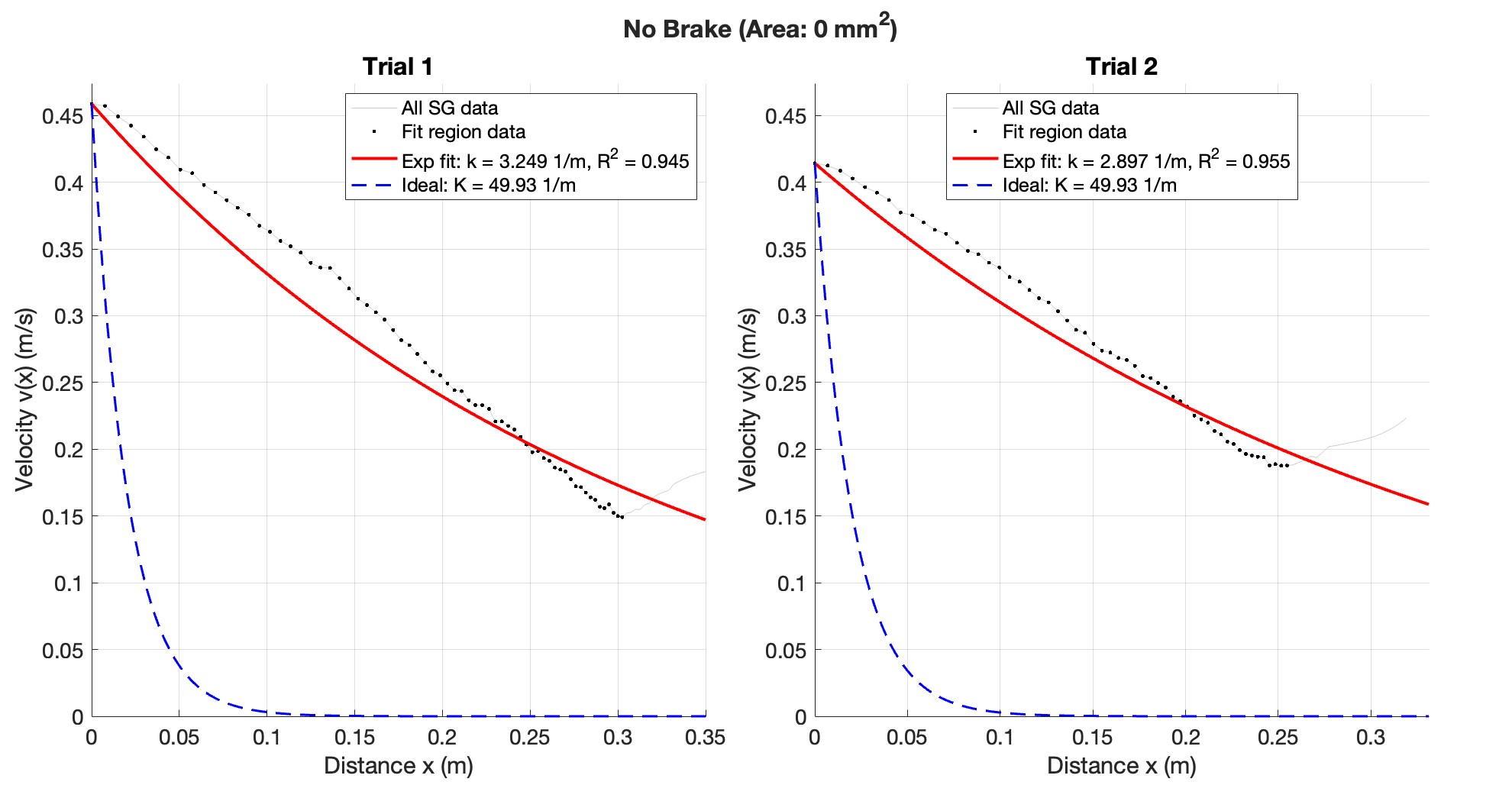

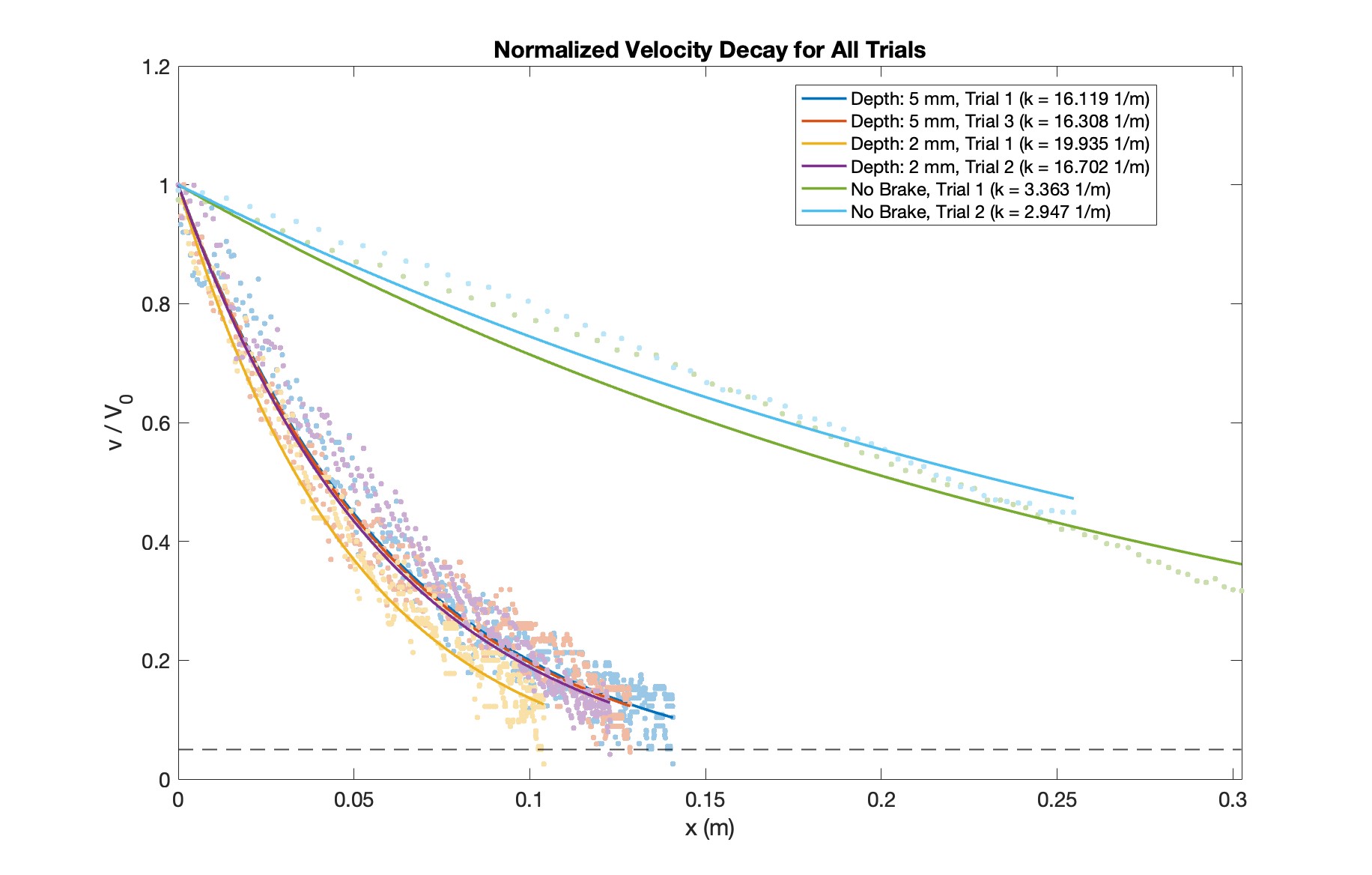

The braking behavior is modeled using a quadratic drag framework, in which the braking force scales with the square of velocity and the projected wetted area of the brake. This formulation leads to an exponential decay of velocity as a function of distance traveled along the water surface. Rather than explicitly modeling every hydrodynamic effect, a single lumped drag constant, (K), is used to capture the combined influence of brake geometry, wetted area, fluid properties, and unmodeled losses. This approach allows braking performance to be characterized using a single physically meaningful parameter that can be directly extracted from experimental data and compared across different brake depths. The full analytical derivation underlying this model is provided in the accompanying report.

Prototype Design and CAD

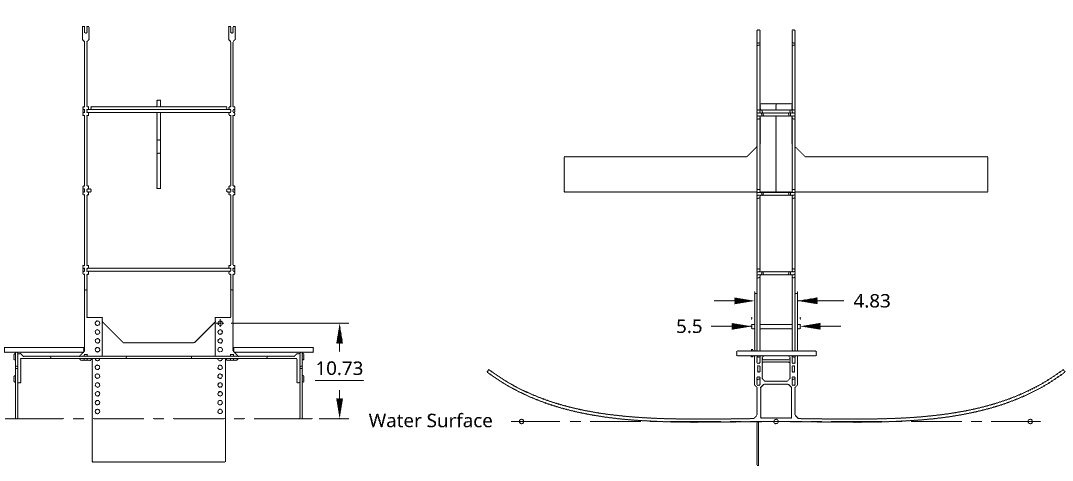

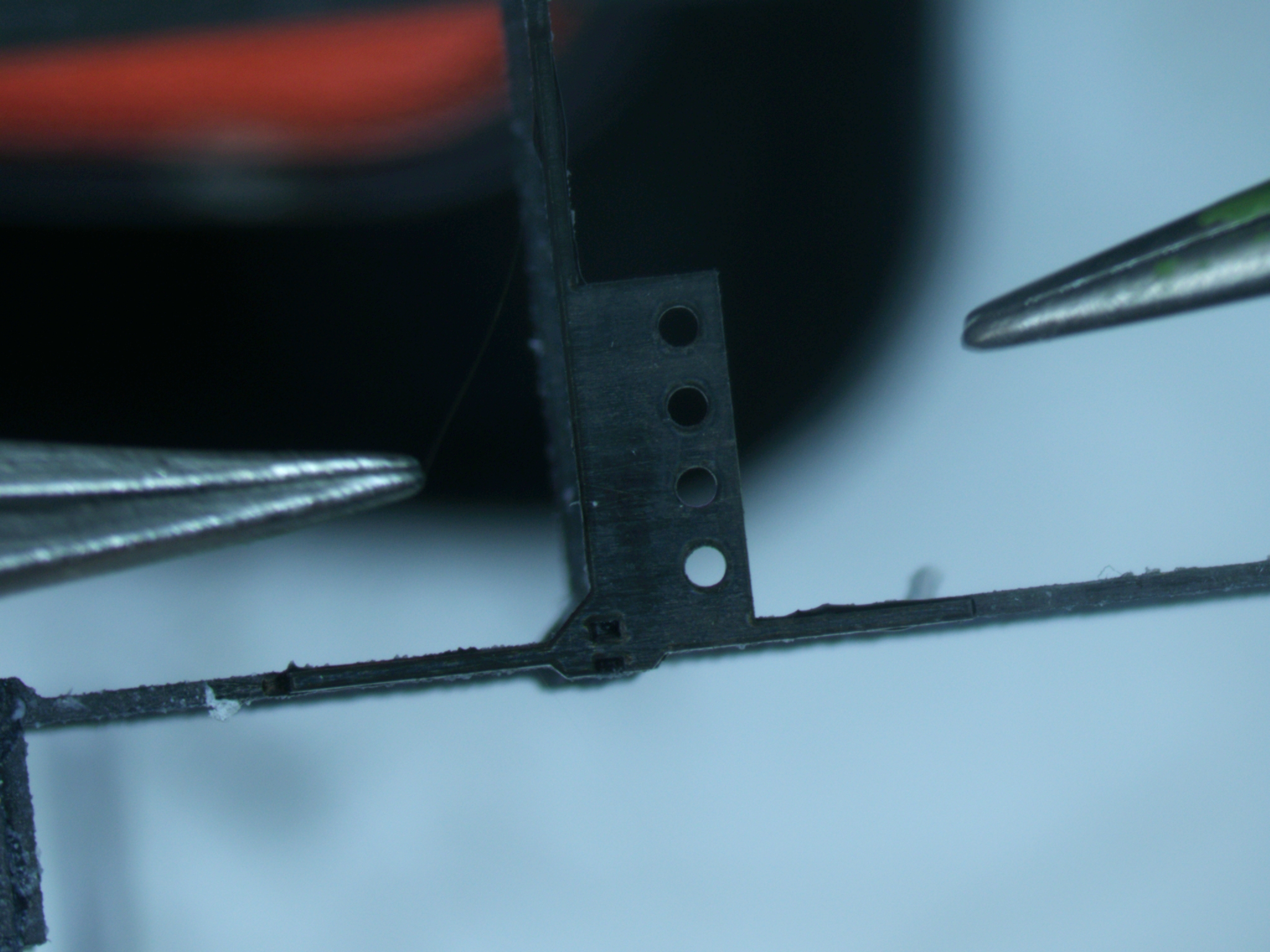

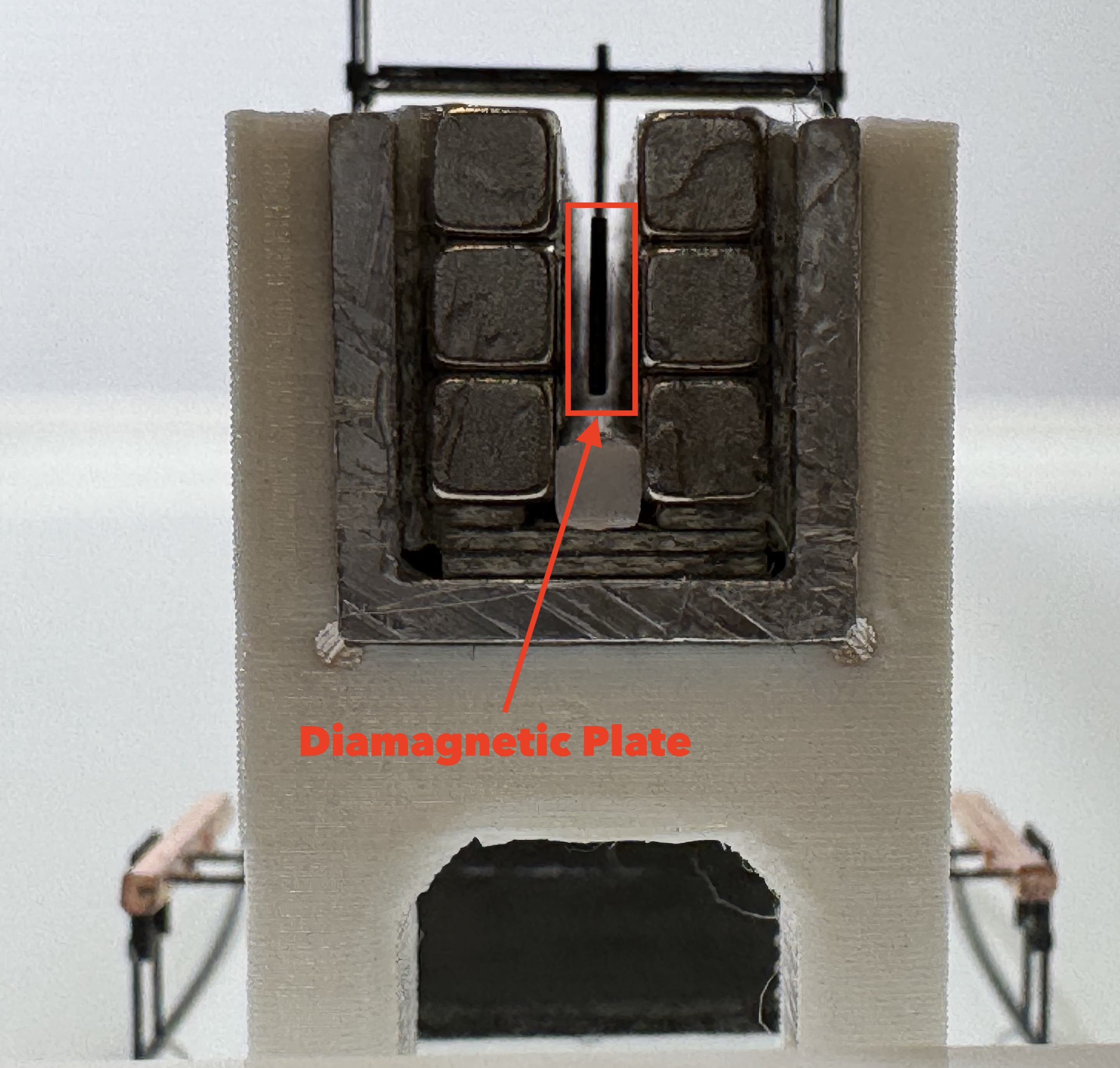

The braking mechanism was designed to mount directly to the existing Gammabot chassis while allowing rapid adjustment of brake immersion depth. A pin-slot architecture enables discrete depth settings without redesigning the surrounding structure, facilitating efficient experimental iteration.

Fabrication & Assembly

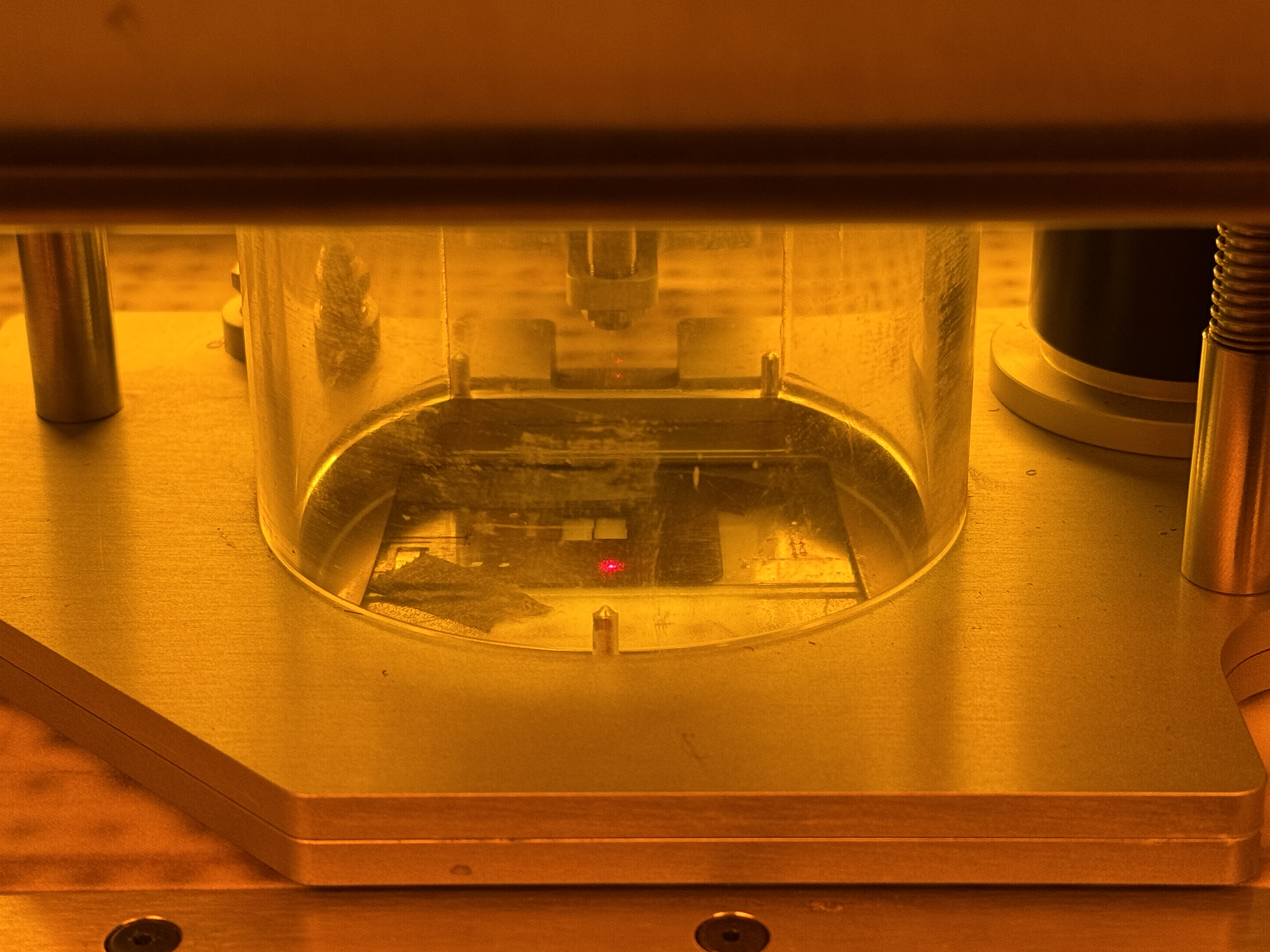

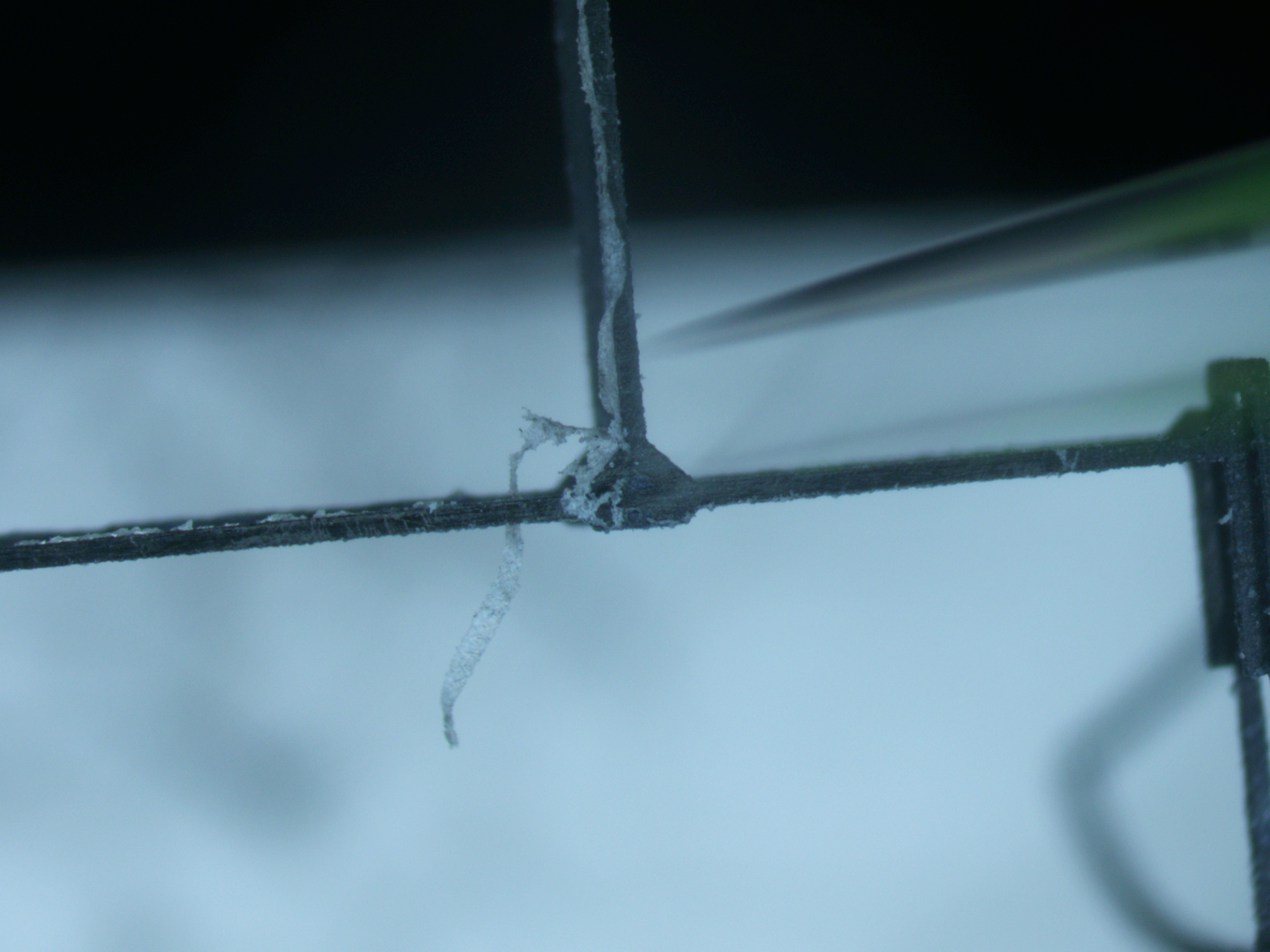

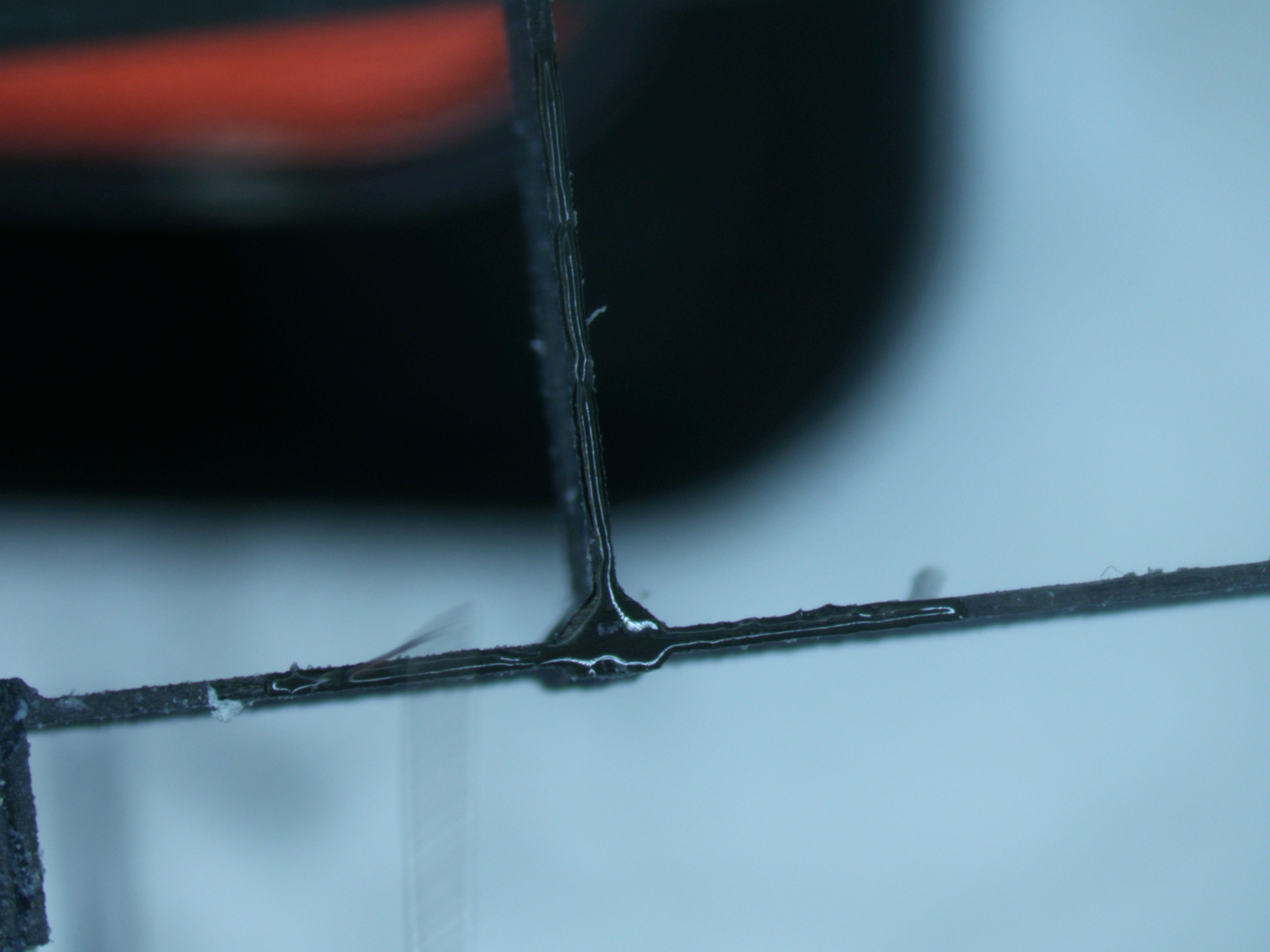

All brake components were fabricated from carbon-fiber–resin laminate stock using laser cutting. This manufacturing method enabled precise control over geometry while maintaining low mass and high stiffness. Laser parameters were tuned to ensure clean edges and consistent hole dimensions for the pin-slot mechanism.

Assembly was performed under magnification due to the small scale of the components. Hydrophobic coatings were locally removed prior to adhesive bonding to ensure reliable joints. The brake plate and mounting brackets were then installed sequentially to achieve the desired immersion depth.

Experimental Setup

Experiments were conducted in a shallow water tank with the magnetic rail spanning the test region. A magnetic test rail is used to constrain the robot to one-dimensional motion while minimizing friction during braking experiments. Diamagnetic levitation supports the robot and provides lateral stability, allowing measured deceleration to be attributed primarily to hydrodynamic drag. The robot was accelerated using a controlled air impulse before entering the braking region. High-speed video was used to track robot position, from which velocity–distance data were extracted for analysis.

Results

Model fit quality: Velocity–distance data from two trials at each brake depth are well captured by an exponential decay model, as evidenced by consistently high R² values across both braked and unbraked conditions.

Braked vs. unbraked comparison: Aggregated fitted decay constants show a clear separation between conditions, with braked trials exhibiting a mean decay constant of approximately 17.27 compared to approximately 3.16 for no-brake trials, corresponding to roughly a fivefold increase in effective drag due to the brake.

Depth dependence: For both braked depths, the fitted decay constant is smaller than the ideal value predicted by design calculations, reflecting real hydrodynamics, tank constraints, and unmodeled losses; however, variation in the decay constant between the two brake depths is limited, despite the expectation that increased wetted area would yield a larger value.

Initial velocity sensitivity: Starting velocities are relatively consistent within each condition. Thus although the no-brake trials begin at approximately 2.5× higher initial velocity than the braked trials, the fitted decay constants within each group remain tightly clustered, indicating weak sensitivity of the decay constant to modest changes in initial velocity.

Stopping distance metric: The distance required to reach 5% of the initial velocity is nearly constant across braked depths and approximately one third of the unbraked value, demonstrating a substantial reduction in stopping distance due to the brake.

Conclusions and Next Steps

The results demonstrate that a compact, passive water brake can significantly improve stopping performance for an interfacial robot. While experimental drag constants did not fully meet analytical targets due to speed and setup limitations, observed trends strongly support the underlying model. Current work is now focusing on achieving higher initial velocities and implementing an actuated braking mechanism to enable on-demand deployment and improved control authority.